Is Japan a country that enjoys a high degree of happiness, or does it suffer from low happiness? And what are the criteria for measuring happiness and well-being levels in the first place?

In this article Rakuten People & Culture Lab Advisor, Well-being for Planet Earth Foundation Representative Director, and preventative medicine researcher Yoshiki Ishikawa will explain how well-being is measured.

This article—The development and history of “metrics” for measuring well-being—is the first part of a two-part series.

Measuring well-being

“Japan ranked 58th on the United Nation’s happiness ranking.”

Such news is announced yearly in late March. That’s because March 20 has been designated the International Day of Happiness and, to coincide with the day, the United Nations has published its World Happiness Report every year since 2012.

Incidentally, although “happiness” is used as an easily understood term for the general public, the report is actually about each country’s well-being.

When I see news like this, I lament Japan’s low level of happiness. But who, exactly, is it that is measuring Japanese people’s happiness? Furthermore, when was “happiness” even defined? Needless to say, it isn’t the ranking that we should be focusing on but rather the definition of well-being. If the definition isn’t satisfactory to Japanese people, then the ranking has no value.

In short, Jim Harter, Gallup Chief Scientist of Workplace Management and Well-Being and one of the designers of the well-being survey items, had this to say:

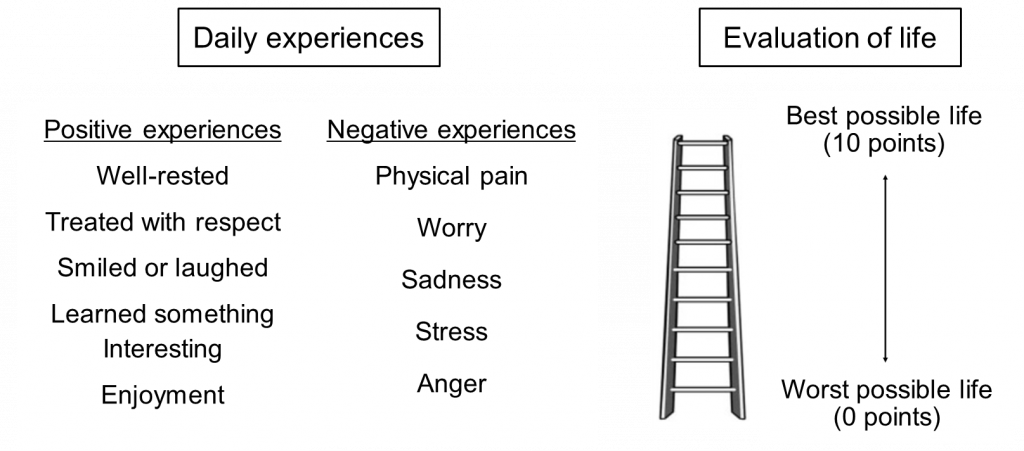

“The well-being survey items ask about two things: experiences and evaluations (see fig. 1). Respondents are asked if they had any of the five positive and five negative experiences during the day prior to taking the survey, and to evaluate their lives on a ten-point scale.”

Most readers will likely wonder why well-being would be measured this way. To understand this, let’s briefly review the history of research into well-being.

What is happiness?

For thousands of years, humanity has been engrossed by the debate over what constitutes happiness. This topic has been the focus of ardent discussion, particularly within the realms of religion and philosophy. But it wasn’t until much later, in the twentieth century, that scientists began to incorporate happiness into their purview of research.

Because the nature of study is to ask questions, it is extremely important to determine what questions to ask. And the question that scientists deemed to ask in their study of happiness was this:

“What are the characteristics of people who say that they are happy?”

I think this is an excellent question because scientists have, in a sense, abandoned directly asking the question “What is happiness?” Instead, they have chosen to focus on the phenomenon of there being people who say that they’re happy.

Despite the short history, there have been some breakthroughs over the decades during which research has been carried out, but I will only discuss the following points as they relate to the definition of well-being that I mentioned earlier.

1) Positive experiences and negative experiences are different concepts

Simply put, having no negative experiences is apparently entirely different from having a positive experience. Therefore, regardless of how much you reduce your negative experiences, it doesn’t mean that, as a result, your positive experiences will naturally increase.

2) Experiences and evaluations are different concepts

Through the research of psychologist, behavioral economist, and 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences winner Daniel Kahneman, who, along with Jim Harter, was involved in the design of the well-being questions, it is well known that people tend to make evaluations based on biased experiences. For example, even if you had a very enjoyable date that made for a positive day, if you were to have a negative experience at the end, such as a fight, you would likely rate the date as a terrible one.

Amid this background, inquiries into well-being currently involve experiences (positive and negative) and evaluations.

Additionally, since 2005, Gallup, the world’s largest public opinion-research company, has been measuring well-being in countries around the world (approximately 1,000 people per country in around 160 countries). Using this data, the United Nations began publishing its World Happiness Report in 2012.

(Continued in Part 2)

So, were you aware that well-being was measured by experiences and evaluations?

In the next article, we will explore the findings from the survey data on well-being and issues regarding the current measurement approach.

This column was an original article contributed by Mr. Yoshiki Ishikawa.