Is Japan a country that enjoys a high degree of happiness, or does it suffer from low happiness? And what are the criteria for measuring happiness and well-being levels in the first place?

In this article Rakuten People & Culture Lab Advisor, Well-being for Planet Earth Foundation Representative Director, and preventative medicine researcher Yoshiki Ishikawa will explain how well-being is measured.

This article—Finding a valid approach to measuring well-being—is the second part of a two-part series.

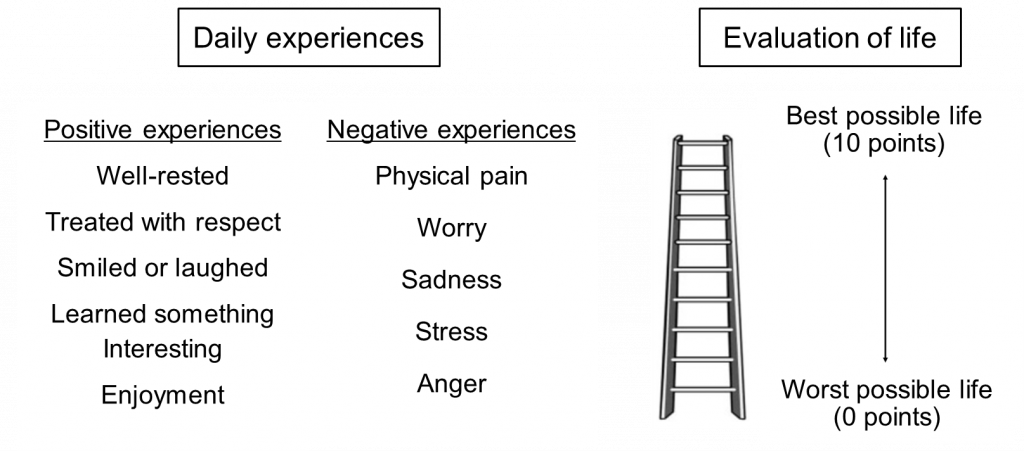

In the previous article I explained how well-being is measured through “experiences” and “evaluations.” In this article I will present findings from survey data to date regarding well-being and the challenges of current measurement methods.

What discoveries have been made?

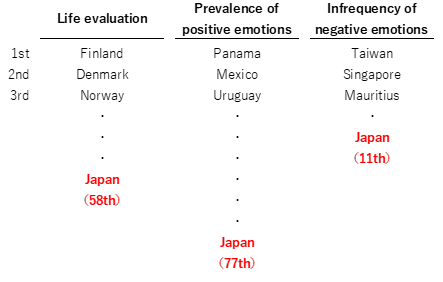

I would like to change the subject now to share with you some of the discoveries we have made so far since we began collecting data related to well-being. First, in terms of simple rankings, we can see the following regional trends.

Countries that highly evaluate life → Northern Europe

Countries with many positive experiences → Central America

Countries with few negative experiences → East Asia

First of all, I should clarify that the United Nations’ happiness ranking I introduced at the beginning of my previous column is only an “evaluation” ranking. Japan, for example, ranks a low 58th in terms of evaluation, but is among the top 11 in the world in terms of how few the number of negative experiences there are in daily life.

In any case, the Gallup survey sheds light for the first time on the fact that “there are significant differences in well-being around the world,” whether in terms of experiences or evaluations.

The question that the researchers next pursued was the degree to which the differences could be attributed to economic factors (GDP and income). Unfortunately, the research has not matured to the point that we can draw any conclusions. Despite the lack of an answer, however, certain findings were made, which can be summarized as follows.

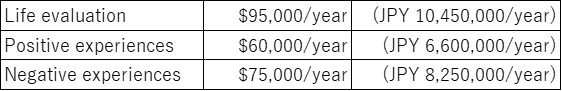

“Economic factors influence life evaluations and day-to-day experiences to a certain extent, but are less relevant beyond a certain threshold.” (Jebb, Tay, Diener & Oishi, 2018).

Put more simply, there is a peak level to the well-being that money can buy. For example, despite some differences by region, it is known that well-being does not increase beyond a certain level of income (see table 1).

* The values displayed in the table are on a per capita basis. For a family comprising N members, it would be necessary to multiply the value by √N. For example, for a family of four, the peak for positive experiences would be 60,000 × √4 = $120,000/year.

So, aside from money, what does it take to increase well-being? According to John Helliwell, Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of British Columbia, it’s “social connections.” The Gallup survey spans a wide range of questions, including the following.

“Do you have a relative or friend who can help you when you are in need of it?”

Those who are able to answer “yes” to this question tend to enjoy a high level of well-being. While it may go without saying that when you are in top form, people are naturally attracted to you. But the instant you fall on hard times, everyone seems to swiftly disappear. That’s why it’s long been said that “a friend in need is a friend indeed.” Incidentally, having such friends is said to have the same impact as increasing your income fivefold.

So, is there a more reasonable definition of well-being?

For better or for worse, Gallup’s global survey has become the international standard for measuring well-being. But is this reasonable? For example, according to the current definition, a ladder is used to evaluate life. This idea of viewing life in terms of a ladder seems very Western in nature.

The original idea for the ladder can probably be attributed to the biblical narrative Jacob’s Ladder, from the Book of Genesis, the Old Testament. The tale features a ladder that, the higher you climbed, the closer you got to heaven. But in Japan, where there is a fear of becoming too happy, simply climbing the ladder was a prospect that didn’t prove appealing. In fact, in the previously mentioned United Nations survey, there was a tendency among Japanese respondents to be reluctant to assign a score of 10 points (the best life).

Instead, Japanese are likely more inclined to compare their lives to a pendulum. While life offers both good things and bad things, the ideal is finding a balance that is “just right” as opposed to seeking “the best.” And throughout Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, they must also have their own unique perspectives on life, one that doesn’t necessarily match the concept of a ladder.

But regardless of how many times we may repeat such criticisms, in reality, it changes nothing. As such, the only way in which to create an “international standard” is by continuing to measure and gather data. If, however, we do nothing, the “life evaluation” of Japanese will forever be measured with a ladder and we will continue to be stigmatized with a 58th place world ranking.

There is, however, still time. Science is always advancing toward the truth (assuming there is one). We will probably never arrive at a perfect definition for how to measure well-being. But there should at least be a definition of well-being that is more valid than the one (by Gallup) we currently have. And if we are able to come up with an approach that is thought to be better, then we will be obligated to gather global data and prove that it is more valid than that gathered through existing measuring methods.

Upon arriving at this acute realization, I, along with my colleagues from around the world, launched a global survey on well-being in 2020. I will share the details of that initiative at another time and wrap up this article here.

It turns out that rankings of well-being by country differ depending on what is measured and which indicators are used to calculate the ranking order. Given the differences in cultural values between regions, finding an approach to measuring well-being that is agreed on many people around the world will likely prove a difficult undertaking.

Accordingly, it is essential that we deepen our understanding of the measuring mechanism used to determine these rankings rather than simply looking at the results and alternating between joy and sorrow.

This column was an original article contributed by Mr. Yoshiki Ishikawa.

Work cited:

Jebb, A.T., Tay, L., Diener, E. & Oishi, A. (2018). Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nature Human Behaviour 2, 33–38.

Reference link

・GALLUP WORLD POLL Global Happiness Center